The sunk cost fallacy is a misguided, ego-driven way of thinking that ruin trading strategies, whether they’re based in technical analysis, fundamentals, or algorithms. Like a cheap cologne, it makes you feel confident, but to everyone else, it stinks. So, naturally, there’s no better way to grasp it than to see how it affects someone else.

The Sunk-Cost Clunker

Imagine you have a friend in the market for a used car. He finds a great listing online, but the car is two hours away. Since he doesn’t have a car (duh), he takes a $100 Uber to go check it out. Once he arrives, he finds that the owner didn’t mention a hideously dinged-up rear end. This thing definitely still drives, but it’s in terrible shape.

Haggling gets him nowhere, so he calls you and asks if he should buy the car.

For you, it’s a no-brainer. Of course not! It’s a rip-off! Who knows what else is wrong with it! There are probably a hundred cars just like it without cosmetic damage!

But he’s fighting for the hunk of junk: “I already spent $100! If I don’t buy it, it’s another $100 to get home, and I still won’t have a car! Plus, the damage is only cosmetic. I could get that repaired. This car can still work – I’ll just have to put a little more money into it!”

You, me and everybody else can see that he’s deluded. But from his perspective, if he turns around now, he’s out $200 with nothing to show for it. So, he starts coming up with reasons to justify his past decisions – the sunk cost fallacy.

But here’s the thing: by buying a car, your friend is making a decision about the future. Any amount he spends today has no bearing on the future value of the car. That’ll be true if he leaves, and more importantly, it’ll STILL be true if he buys the car! Except he’ll be in for much, much more than just $200.

Sunk Cost Fallacy? Not All is Lost

Now, let’s step into a world with just as many clunkers: the market.

When an investment goes south, we tend to want that particular investment to work out. We want restitution. We want to be right. Our egos want these things so badly, we can forget what we really came here for: a good return.

In the same way, your friend didn’t set out wanting to buy that exact, dinged-up car. He wanted one that’s safe, with good gas mileage, less than 50,000 miles on it, etc. It was only after he invested time and money into that particular car that he was blinded by the sunk cost fallacy.

So, when your friend goes to check out his next car, he needs to examine his framework for making decisions: his strategy. Perhaps he was too quick to pay for an Uber after only seeing a car online. Perhaps he had so many strict criteria – make, model, mileage – that the only car that fit them was the clunker. As we look at the chain of events, the importance of how one makes decisions becomes more and more important.

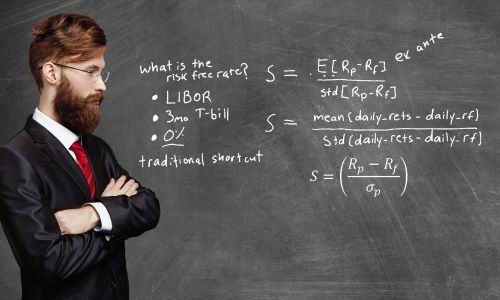

When investing, we don’t get returns by being right every time. We get them by using the right investing strategies: questioning how and why we make decisions.

Driving it Home

In the car analogy, your friend was investing, whether he realized it or not. The steps he took mirror those of many traders with short careers:

- He looked online for listings. Traders watch the news.

- He saw a listing. Traders find interesting opportunities.

- He wanted a good deal. Traders want a good return.

- He took a two-hour Uber. Traders spend time doing research.

- He spent $100. Traders buy in.

- He rationalized how he would fix up the car. Traders come up with explanations about how a security will turn around.

- He wanted to avoid “losing” $100 for no reason. Traders hate closing out trades in the red.

In every form of trading, decisions can create value, but they’re always in an uphill battle with human nature. Learning how to make decisions about strategies, like when to trust algorithmic trading or technical analysis, can be the single most valuable decision you make.

Learn more about fractalerts. Fill in the form on our home page and a member of our team would be happy to give you a call or engage via email. Follow our trades. Leave the math to us. To simply learn more about our process, check out our “The Science” page.

-

The rhytm beneath the noise

-

You Don’t Need a Trading Style. You Need an Edge.

-

Consistency Isn’t the Goal—It’s the Outcome

-

What 2 Quadrillion Data Points Told Us

-

Math and Physics-Based Trading in Any Market Condition

-

Do not worry about anomalies

-

Consistency should not be the goal. Consistency should be the result.

-

Stop canceling fridays

-

The Elliott Wave Forecast is Subjective, Bias Driven And Backwards looking

-

Finding patterns in market data